As it is now customarily posed in taxidermy, the Great Auk—a three-foot tall, penguin-like bird—stands upright on black webbed feet, with its wings, politely, reservedly, held by its side. The story of this creature complicates a wishful theory about avoiding extinction.

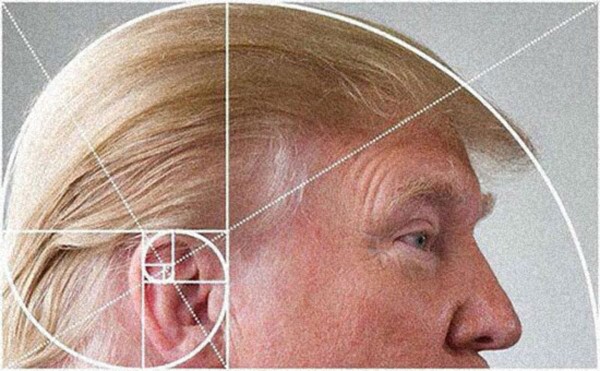

The wishful theory is one of those—one of many—that models the world in terms of information exchanges. Things and beings are understood in terms of their interplay with other things and beings, and this sort of information exchange potentially trumps that of ubiquitous digital media since the exchanges can happen between anything. As the cyberneticist Gregory Bateson argued, a man, a tree, and an axe is an information system. The presumption is that more exchanges in this information system—between properties, pencils, dogs, Great Auks, shipping containers, molecules people, etc.—make the pool of information more robust, resilient and intelligent. Everything in the world is—like the genetic material of a species—sturdier when it is mixed and crossed in garden-variety mongrels. In relaxed versions of the theory, information is not the atomised elementary particle of a comprehensive, universal whole—a cybernetic God or a fairy tale Gaia. Rather, there is a habit of mind or loose tendency to make counterbalancing moves that might stave off one or another planetary extinction. Isolation and isomorphism are stupid and dangerous. Interplay is smarter and more stable.

Yet against every principle of the intelligence-through-interplay theory, the Great Auk was marvellous not because of a tendency to interbreed with other sorts of birds. Isolating its genetic material by living and breeding on one of a few islands in the cold North Atlantic, it seemed to favour the enclave. It was like a human who saw no need to be a “joiner”. It would not have engaged in group therapy. It would not have lobbied in groups demanding recognition of its “identity”. It would not have married a dentist. It was a strange bird with the distinction of waiting on an island to mate with another strange bird. One admires the way the husband and wife Auk fussed over their doomed offspring. One is inspired to strain life into a potent consommé of thought and existence that can be finished off in one quick sip. It is as if one kind of isolation is stupid and another is beautiful – or at least something that looks like a Great Auk.

Further complicating the theory is the incredible success and resilience of other more aggressive, or predatory forms of stupidity and isolation. Seventeenth-century British explorers and travellers went out of their way to kill off Auks on the islands where they bred. They would put a couple of them to boil in a pot and then light a couple of them on fire underneath the pot because the bird’s oily bodies made good fuel. The explorers congratulated themselves for discovering something like geese mixed with cords of wood, both of which were easily herded into pens. One creature was weakened because its existence represented a shrinking pool of information. Another ugly, white, furless, featherless creature survived, even dominated, precisely because of its ability to shrink that information pool.

If extinctions often occur after protracted periods of tedium and brief periods of panic, the world’s persistent accumulations of urbanising development at the expense of the environment might provide the tedious part, while their resulting atmospheric changes have already modelled trends of panic. Exacerbating this condition, the most recent accelerating waves of development are often repeatable, almost infrastructural spatial products and free zone world cities designed to have more and more exemptions from environmental regulation. The wishful theory would regard these large quantities of isolated buildings and isomorphic enclaves as arrangements producing less information exchange and therefore less intelligence. And, learning from both Auks and humans, there is something about the very repeatability of these spaces that makes them less like the very particular Auk and more like the resiliently, insistently stupid human.

Yet, in the spreading matrix of repeatable development patterns, the very stupidity of the multipliers makes the wishful theory seem potentially viable. These spaces are full of multipliers that, if altered, might have viral population effects. Any new multiplier positioned in this population can become contagious. Any switch can rewire multiple relationships. Might small patterns of interplay become equally contagious? For instance, to dial up the interplay, rather than buying one house and sitting alone inside – happy with individual territory but worried about pending catastrophes – one would always buy more than one house. In other words, every house is attached to another offsetting house. In flood prone areas, two mortgages that together result in a movement from low to high ground are streamlined and given special rates that also lower everyone’s flood insurance costs. Or failed and foreclosed properties in distended ghost suburbs are linked to denser properties and have a share in each other’s enterprise. No property is ever worth nothing, or less than nothing as it often was in the financial crisis. A portfolio of spatial variables is traded in a market where risks and rewards are more tangible and stabilising. One could not only add buildings but also take them away – put the building machine in both forward and reverse. Rather than shocking crashes or perfect homeostasis, little machines of counterbalancing spatial variables can target, contract or reposition development. That is the wishful theory.

Satisfying as it might be to imagine the Auk fending off humans by evolving the perfect set of teeth to sink into his white ass, a more effective survival technique might, in the end, have been to carry a germ that made him sick. One can perhaps never hope to confront authoritarian concentrations of power armed only with righteous opposition (or teeth). One needs organisational germs that use the very structure of power as their carrier. But in addition, one needs a silver-tongued Auk with infectious stories to engage the human brain - narrative germs, like rumours and desires that, in a turnabout, begin to herd the human mind into a useful position. The stories of interplay must seem as magical and selfishly motivated as the cords of wood that transported themselves.

Otherwise something hungry will have you for a meal. And nothing will happen before or after you are eaten. No special music. The world will smell like it always does – like machine oil, skin and a hot TV at 3:30 in the afternoon. But you will not be able to smell it.