Extrastatecraft: Dubai

Kanu Agrawal, Melanie Domino, Brad Walters eds., Perspecta 39, Re_Urbanism: Transforming Capitals — 2007

Download Full Article (PDF)

Reprinted as “Stadtstaatskunst,” in Elisabeth Blum and Peter Neitzke eds., Dubai: Stadt aus dem Nichts (Berlin: Birkhauser Verlag, 2009).

Excerpted and updated as “World City Double,” in Roldolphe El-Khoury and Edward Robbins, ed., Shaping the City: Studies in History, Theory and Urban Design (Routledge, 2013).

Dubai. The hot spot where adventurers play the world’s most dangerous games of gold, sex, oil, and war.

Dubai. A wild, seething place in the sunbaked sands of Arabia, where billion-dollar carpetbaggers mix explosive passions with oil. And exotic pleasures pay fabulous dividends.

Whores, assassins, spies, fortune hunters, diplomats, princes and pimps—all gambling for their lives in a dazzling, billion-dollar game that only the most ruthless and beautiful dare to play.

—jacket copy from Dubai, by Robin Moore, author of the The French Connection

In 1976, after The Green Berets, The French Connection and several other global intrigues, Robin Moore published a novel titled Dubai. The novel opens in 1967. Fitz, the monosyllabic hero and American intelligence officer, is fired over his pro-Palestinian/anti-Semitic remarks that appear in the press just as the Six Day War is launched. Dubai, like the not-yet-middle-aged protagonist, is still fluid and unsettled. It is still a place where adventures and deals are flipped and leveraged against each other to propel small syndicates to fame and fortune. Fitz quickly scales a succession of events in the UAE’s history during the 1970s. He arrives when a handful of hotels and the new Maktoum Bridge across Dubai Creek are among the few structures that appear in an otherwise ancient landscape, one that has changed very little in the centuries that Dubai has been an entrepôt of gold trade and a site for pearl diving. Just on the brink of Sheikh Rashid’s plans for an electrical grid, the air-conditioning in Fitz’s Jumeirah beach house must struggle against the 120 degrees and 100 percent humidity by means of an independent generator. The story proceeds by moving in and out of air-conditioning, syndicate meetings, and sex scenes in the palaces of the Sheikh or in hotel cocktail lounges between Tehran, Dubai, and Washington. The tawdry glamour of tinkling ice and Range Rovers is frequently interrupted for a number of rough and tumble adventures that are evenly distributed throughout the book. The discovery of oil has already propelled the development of the Trucial States (states that have made maritime truces with the original oilmen, the British).

Fitz’s first escapade uses the old gold economy to capitalize on the new oil and real estate economy. The syndicate’s dhow (the traditional vessel on the creek) is souped up with munitions and technology that Fitz has illegally stolen from the American military. Dubai is an old hand at smuggling, or what it likes to call “re-export,” during embargoes or wars that are always available in the Gulf. Shipping gold to India usually involves armed encounters in international waters. The dhow’s U.S. military equipment vaporizes the Indian ships, thus trouncing piracy and resistance to the free market. Fitz plunders enough money to bargain with the sheikh for shares of an oil enterprise in Abu Musa, an island in the Gulf halfway between Dubai and Iran. He has enough money left over to finance a saloon, equipped with old CIA bugging devices and an upstairs office with a one-way viewing window. From this perch Fitz entertains the growing number of foreign businessmen who are laying over in Dubai and the growing number of Arab businessmen who want to see and approach Western women. He continues in his plot to become a diplomat to the new independent federation of Trucial territories, the United Arab Emirates, to be established in 1971.

Fitz (like Dubai) gets things done. With a wink and a nod Sheikhs and diplomats reward him. He even manages to single-handedly crush a communist insurgency in the desert. (Most Robin Moore novels fight the old Cold War fight, although his most recent forays take on the new devil: terrorism.) In the novel, America’s heroic Cold War deeds in the Gulf have made us simple lovable heroes with both naughtiness and vulnerability. Fitz wisely realizes that most political activities are not vetted through recognized political channels. In Dubai, the naughty hero formula even goes one dyspeptic step further in engineering sympathy for the character and happily signally the end of the novel: Fitz hurts his leg fighting the insurgency. Despite his wounds and even though he has contributed a suitcase full of money in campaign contributions, he doesn’t get the ambassadorship. He is unfairly tainted with the centuries of regional piracy and the only too recent hotel-bar intrigues. Nevertheless, Fitz gets the girl in the end, the daughter of a diplomat living on the Main Line in Philadelphia, and they begin to plan their middle-aged life “on the creek” in Dubai.

November: conversation at Karma with Emmanuel Olunkwa and Ricky Ruihong Li

November — February 21, 2023

Trabar Sin Soluciones/Working Without Solutions, Interview

Federico Ortiz, Ushma Thakrar, Negacion/Refusal, Escuela de Arquitectura Universidad San Sebastian — December 5, 2022

Direct (Dispositional) Action

Martin Beck, Beatrice von Bismarck, and Sabeth Buchmann, Ilse Lafer, eds., Broken Relations: Infastructure, Aesthetics, and Critique (Spector Books). — November 1, 2022

Levittowns: Dialogue with Kenismael Santiago-Pagan

Pairs — June 29, 2022

Non-Growing: Translation Subtraction, Interview Medium Design

Ehituskunst #61/62, Estonia — July 1, 2022

El Ejido

Ida Soulard, Abinadi Meza, and Bassam El Baroni, eds., Manual for a Future Desert (Milan: Mousse Publishing). — 2021

Expansions Venice Biennale

2021

Release

Esperanto Culture Magazine — April 1, 2021

21st Century City

“Designing Infrastructure,” in Suzanne Hall and Ricky Burdett eds., The Sage Handbook of Urban Sociology: New approaches to the twenty-first century city (London: SAGE/LSE). — 2017

A Man a Tree and and Ax

Lola Sheppard and Maya Przybylski, eds., Bracket: At Extremes (Barcelona: Actar). — November 1, 2016

ARQ 92: Excepiones

April 1, 2016

The Dispositions of Theory

James Graham, ed.,The Urgencies of Architectural Theory (New York, GSAPP Books) — 2015

Documenta 14 Daybook

Documenta 14: Daybook, (Prestel, 2017) — July 1, 2017

Encounters with Climate

“Encounters with Climate” in James D. Graham, ed., Climates: Architecture and the Planetary Imaginary (Columbia Books on Architecture and the City/Lars Muller Publishers, 2015). — 2016

Everywhere

Zivot: Transmigrancy, 12/2017.101 — December 1, 2017

The Histories of Things That Don’t Happen and Shouldn’t Always Work

Arjun Appadurai and Arien Mack, eds., Failure: Social Research International Quarterly — September 1, 2016

I Kan Beholde Jeres States_Borgerskab For Jer Selv

Arkitekten 06 — August 1, 2018

Impossible

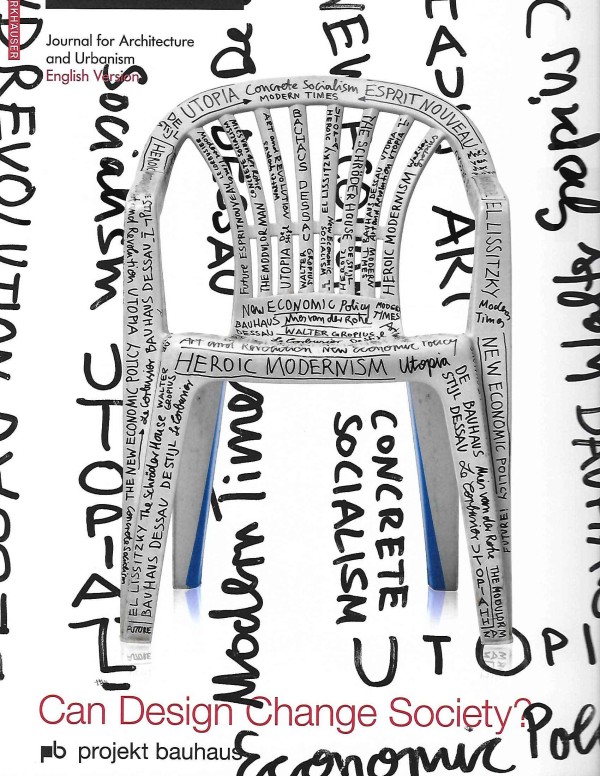

Pedro Gadanho, Joao Laia and Susana Ventura, eds., Utopia/Dystopia: a Paradigm Shift in Art and Architecture — March 1, 2017

Infra-read: Interview by Jesse Seegers

Pin-Up — May 1, 2016

Foreword

Nicholas De Monchaux, Local Code: 3659 Proposals about Data, Design and the Nature of Cities, (PAP) — 2016

Matrix Space

Mohsen Mostafavi, Ethics of the Urban: The City and the Spaces of the Political (Harvard GSD, Lars Muller) — 2017

Park in Allan Sekula: Okeanos

Daniela Zyman and Cory Scozzari, Allan Sekula: Okeanos (Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary Sternberg Press, 2017) — July 1, 2017

On Dispositions and Form Making: A Conversation Keller Easterling and Andrea Phillips

Paul O’Neill, Lucy Steeds and Mick Wilson, eds. How Institutions Think: Between Contemporary Art and Curatorial Discourse (MIT Press) — 2017

Review: Burdens of Linearity by Catherine Ingraham

Constructs — 2006

Space as a Medium of Innovation, Interview with Berndt Upmeyer

MONU: Magazine on Urbanism, #26, Spring 2017 — May 1, 2017

Split Screen

Ilke and Andreas Ruby, eds., Infrastructure Space, Holcim Foundation (Ruby Press). — 2016

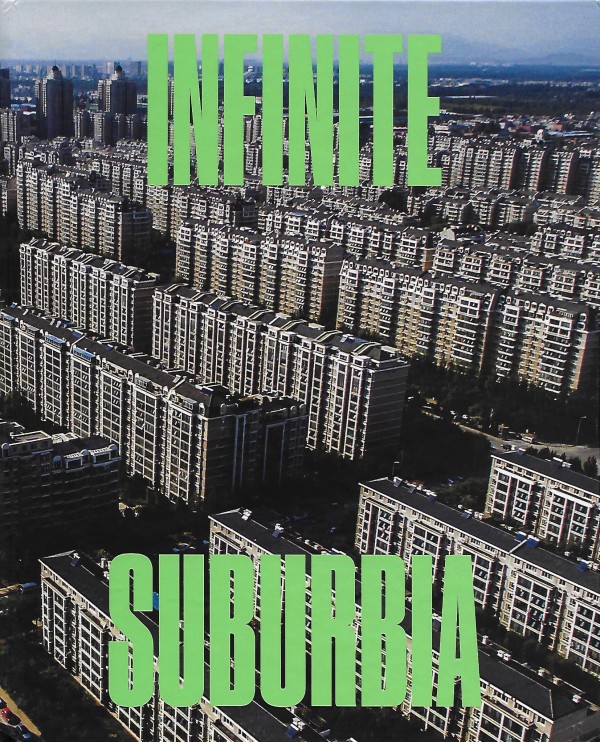

Subtracting the Suburbs

Infinite Suburbia, Alan Berger, Joel Kotkin, eds. (New York, PAP) — 2017

Suburbia in Reverse

Stephanie Hessler, ed. Tidaletics, MIT Press, 2018 — March 1, 2018

Superbug

Log 39 Spring 2017 — March 15, 2017

Terra Incognita

Unthought Environments — 2019

The Switch

Imre Szeman and Jeff Diamanti, eds., Energy Culture: Art and Theory on Oil and Beyond (West Virginia University Press). — 2019

Things That Don’t Always Work

Ryan Bishop, Kristoffer Gansing, Jussi Parikka and Elvia Wilk, eds., Across and Beyond—A Transmediale Reader on Post-digital Practices, Concepts, and Institutions — 2016

Things That Shouldn’t Always Work

ERA 21 Post Digitalni Architektura — 2019

To Play Space

Perspecta 51: Medium — October 1, 2018

Protocols of Interplay

Volume: The System — April 1, 2016

Interview

Arqa — 2011

World City Doubles

Roldolphe El-Khoury and Edward Robbins, ed., Shaping the City: Studies in History, Theory and Urban Design (Routledge). — June 1, 2013

Fresh Fields

Coupling: Pamphlet Architecure 30 Infranet Lab/Lateral Office (New York: Princeton Architectural Press) — 2011

Megabuilding

Architektura 4, 163 (Kwiecien) — 2009

In the Briar Patch

Jonathan Solomon ed., Sustain and Develop 306090 Volume 13 (New York: 306090, Inc.) — 2009

Intermediate Points of Interest

Gaby Brainard, Rustam Mehta, and Thom Moran eds., Perspecta 41 Grand Tour — 2008

Rumor

Megan Born and Lily Jencks, eds, Via: Dirt, University of Pennsylvania — 2012

The Agent: Interview with Neeraj Bhatia

The Agent No. 0 — May 1, 2014

The Knowledge

Volume 13: Ambition — 2007

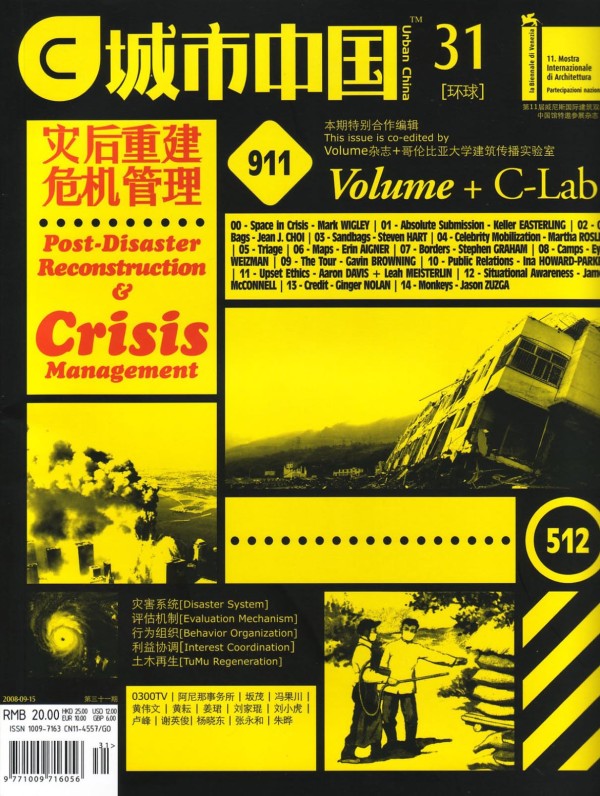

Absolute Submission

Crisis, a collaboration of C-Lab and Urban China — September 15, 2008

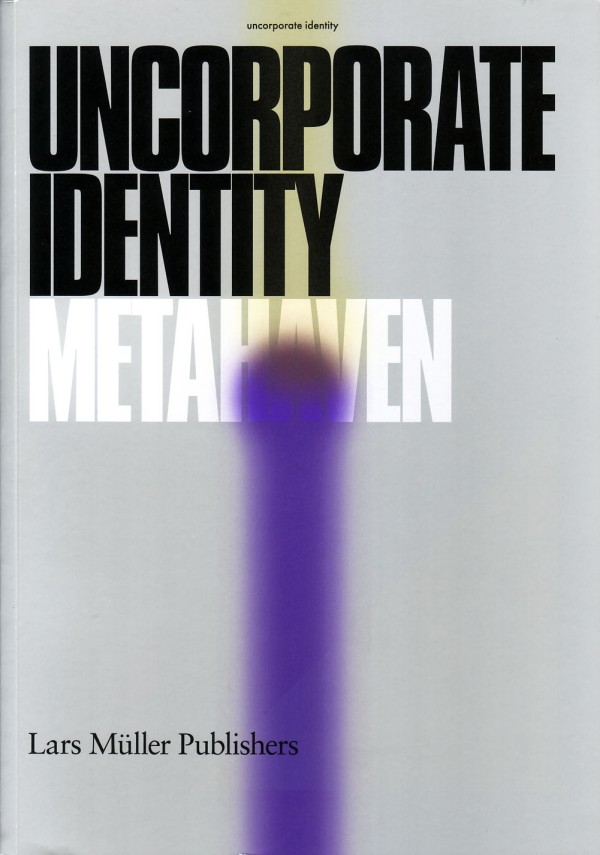

Come to Things

Metahaven and Marina Vishmidt, eds., Uncorporate Identity (Zürich: Lars Müller) — 2010

Disposition: In_site

In_Site: A Dynamic Equilibrium, In_Site 05 (Friessen) — 2007

Foreword

Young Architects 7: Situating, catalog of Architectural League's Young Architects competition and exhibition (New York: Princeton Architectural Press) — 2006

Pandas: A Rehearsal

Cornell Journal of Architecture — 2011

Other Aggressions and Maneuvers

The Last Mile, photography catalog Satya Pemmaraju (Gallery SKE) — 2007

Subtraction

Perspecta 34: Temporary Architecture (MIT Press) — 2003

A-Ware

Journal of Architectural Education, special digital issue — January 1, 2002

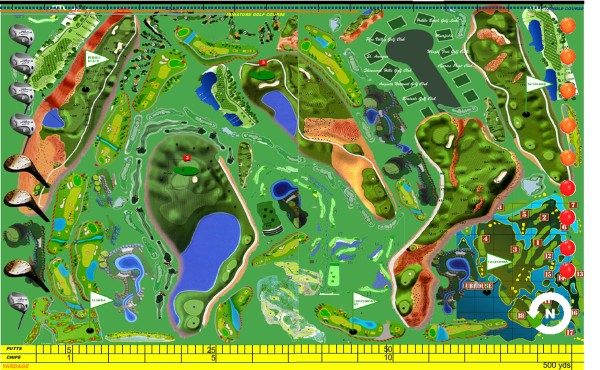

Wildcards: a Game of Orgman

Metalocus 5 — 2000

Interchange and Container: The New Orgman

Perspecta 30 Settlement Patterns — 1999

A Short Contemplation on Money and Comedy

Thresholds 18 (MIT) — 1999

Distributive Protocols: Residential Formations

Beauty is Nowhere: Ethical Issues in Art and Design (Routledge) — 1998

American Town Plans excerpt

ANY — 1993

Siting Protocols

Peter Lang, ed., Suburban Discipline (Storefront Books) — 1997

Call it Home

Assemblage 24 — 1994

Perceiving Action

Offramp, SCI-ARC Journal, vol. 1, no. 5 — 1993

Switch

City Speculations (New York: Princeton Architectural Press) — 1996

Non-statecraft

Maghreb Connection: Movements of Life Across North Africa (Barcelona: ACTAR) — 2007

Graduate Sessions No. 9

Syracuse University — 2010

Not Everything

Volume 2: Not Everything — 2005

Without Claims to Purity

aX, vol. 1+2 (Winter) — 2008

Architect-at-Large

Volume 1 — 2005

The Activist Entrepreneur

John Wriedt ed., Architecture: From the Outside In (New York: Princeton Architectural Press) — 2010

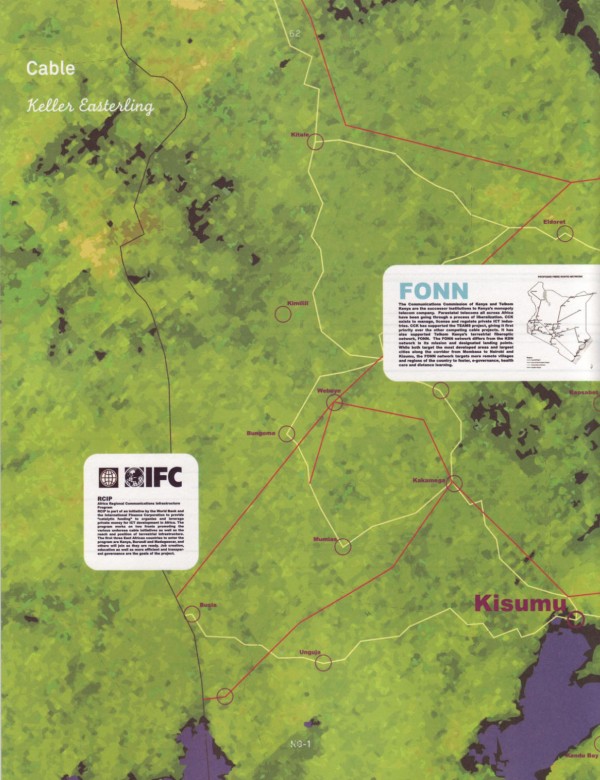

With Satellites: Remote Sending in South Asia and the Middle East

Brian McGrath and Grahame Shane eds., AD, Sensing the 21st Century: Close-up and Remote Vol. 75 No. 6 — 2005

Offshore

Anselm Frank and Eyal Weizman, eds., Territories: the Frontiers of Utopia and Other Facts on the Ground (Berlin: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König) — 2004

Orgman

Stephen Graham, ed., The Cybercities Reader (London: Routledge) — 2003

Unsettling Matter Gaining Ground, Dialogue with Imani Jacqueline Brown

Carnegie Museum of Art — October 5, 2023 – January 7, 2024