A scrotum moves on its own—adjusting itself in some stage of excitement. The nape of a neck grows a drifting crop of its own hair. A lifted arm allows an underarm some access to the larger world. Seen directly from below, the balls and hoses of male genitalia dangle next to the split cheeks of a bottom. A womb manages the pressure of concentric stretching bags of fluids and moving solids.

Humans are sad creatures somehow, with rigid skeletons and tense, stringy muscles giving shape to bulges and tentacles that are marooned in different parts of the body. Separated as they are and stuck off in pockets of skin, these bulges, rarely acting in concert, exercise their limited sentience in stiff and routine performances.

The organism has the potential to be so much more cephalopodic, with a nervous system distributed across its surface area and a shape that is a fluid negotiation of salinity and electricity. There are other ways of moving, touching, and sensing in a body filled with countless overlapping trial-and-error processes. But for humans, surrounded not by water but by less viscous air, it seems that gravity is turned up way too high. The whole body tends to sink and fall or need constant propping up in chairs.

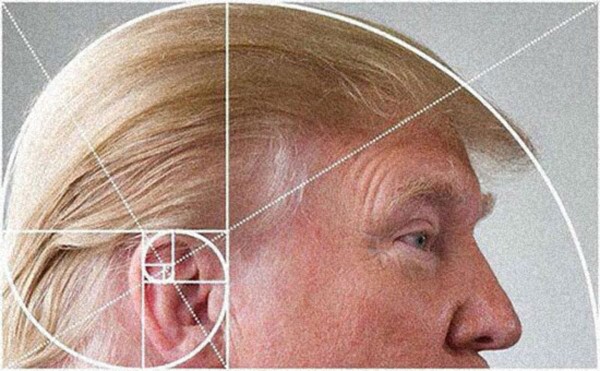

Another of the body’s knobby outcroppings, the one that houses the brain, puts eyes and mouth in close proximity. Privileging visual evidence and lexical expressions, it is very good at calling the names of things with shapes and outlines that are positioned in front of it. The body rocks back and forth, advancing forward and absorbing this nominative, mostly two-dimensional world, and it likes things that reinforce a preference for vision. This is what humans usually seem to be, at least so far. ...

November: conversation at Karma with Emmanuel Olunkwa and Ricky Ruihong Li

November — February 21, 2023

Trabar Sin Soluciones/Working Without Solutions, Interview

Federico Ortiz, Ushma Thakrar, Negacion/Refusal, Escuela de Arquitectura Universidad San Sebastian — December 5, 2022

Direct (Dispositional) Action

Martin Beck, Beatrice von Bismarck, and Sabeth Buchmann, Ilse Lafer, eds., Broken Relations: Infastructure, Aesthetics, and Critique (Spector Books). — November 1, 2022

Levittowns: Dialogue with Kenismael Santiago-Pagan

Pairs — June 29, 2022

Non-Growing: Translation Subtraction, Interview Medium Design

Ehituskunst #61/62, Estonia — July 1, 2022

El Ejido

Ida Soulard, Abinadi Meza, and Bassam El Baroni, eds., Manual for a Future Desert (Milan: Mousse Publishing). — 2021

Expansions Venice Biennale

2021

Release

Esperanto Culture Magazine — April 1, 2021

21st Century City

“Designing Infrastructure,” in Suzanne Hall and Ricky Burdett eds., The Sage Handbook of Urban Sociology: New approaches to the twenty-first century city (London: SAGE/LSE). — 2017

A Man a Tree and and Ax

Lola Sheppard and Maya Przybylski, eds., Bracket: At Extremes (Barcelona: Actar). — November 1, 2016

ARQ 92: Excepiones

April 1, 2016

The Dispositions of Theory

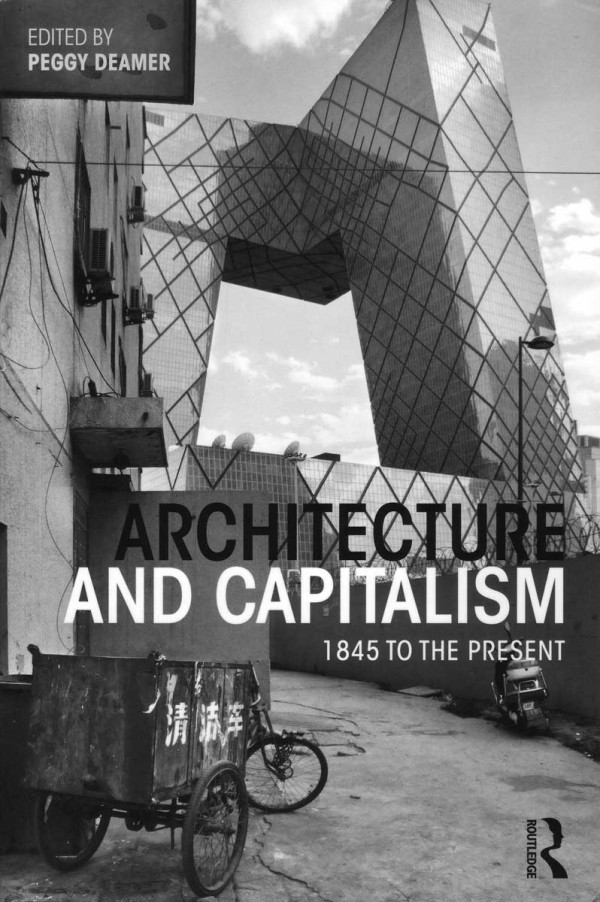

James Graham, ed.,The Urgencies of Architectural Theory (New York, GSAPP Books) — 2015

Documenta 14 Daybook

Documenta 14: Daybook, (Prestel, 2017) — July 1, 2017

Encounters with Climate

“Encounters with Climate” in James D. Graham, ed., Climates: Architecture and the Planetary Imaginary (Columbia Books on Architecture and the City/Lars Muller Publishers, 2015). — 2016

Everywhere

Zivot: Transmigrancy, 12/2017.101 — December 1, 2017

The Histories of Things That Don’t Happen and Shouldn’t Always Work

Arjun Appadurai and Arien Mack, eds., Failure: Social Research International Quarterly — September 1, 2016

I Kan Beholde Jeres States_Borgerskab For Jer Selv

Arkitekten 06 — August 1, 2018

Impossible

Pedro Gadanho, Joao Laia and Susana Ventura, eds., Utopia/Dystopia: a Paradigm Shift in Art and Architecture — March 1, 2017

Infra-read: Interview by Jesse Seegers

Pin-Up — May 1, 2016

Foreword

Nicholas De Monchaux, Local Code: 3659 Proposals about Data, Design and the Nature of Cities, (PAP) — 2016

Matrix Space

Mohsen Mostafavi, Ethics of the Urban: The City and the Spaces of the Political (Harvard GSD, Lars Muller) — 2017

Park in Allan Sekula: Okeanos

Daniela Zyman and Cory Scozzari, Allan Sekula: Okeanos (Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary Sternberg Press, 2017) — July 1, 2017

On Dispositions and Form Making: A Conversation Keller Easterling and Andrea Phillips

Paul O’Neill, Lucy Steeds and Mick Wilson, eds. How Institutions Think: Between Contemporary Art and Curatorial Discourse (MIT Press) — 2017

Review: Burdens of Linearity by Catherine Ingraham

Constructs — 2006

Space as a Medium of Innovation, Interview with Berndt Upmeyer

MONU: Magazine on Urbanism, #26, Spring 2017 — May 1, 2017

Split Screen

Ilke and Andreas Ruby, eds., Infrastructure Space, Holcim Foundation (Ruby Press). — 2016

Subtracting the Suburbs

Infinite Suburbia, Alan Berger, Joel Kotkin, eds. (New York, PAP) — 2017

Suburbia in Reverse

Stephanie Hessler, ed. Tidaletics, MIT Press, 2018 — March 1, 2018

Superbug

Log 39 Spring 2017 — March 15, 2017

Terra Incognita

Unthought Environments — 2019

The Switch

Imre Szeman and Jeff Diamanti, eds., Energy Culture: Art and Theory on Oil and Beyond (West Virginia University Press). — 2019

Things That Don’t Always Work

Ryan Bishop, Kristoffer Gansing, Jussi Parikka and Elvia Wilk, eds., Across and Beyond—A Transmediale Reader on Post-digital Practices, Concepts, and Institutions — 2016

Things That Shouldn’t Always Work

ERA 21 Post Digitalni Architektura — 2019

To Play Space

Perspecta 51: Medium — October 1, 2018

Protocols of Interplay

Volume: The System — April 1, 2016

Interview

Arqa — 2011

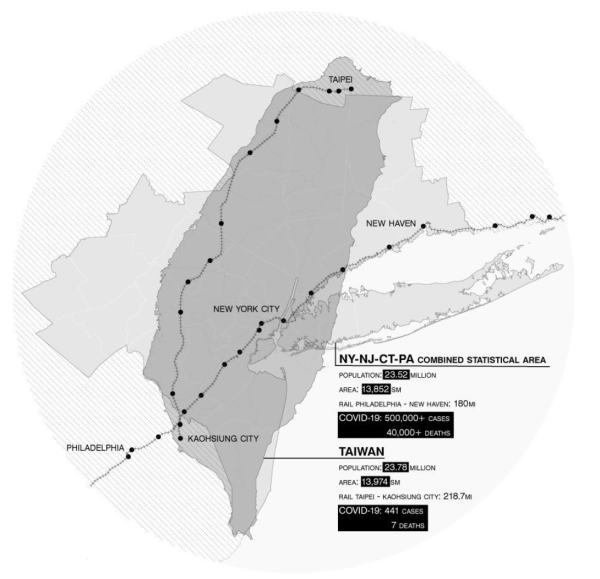

World City Doubles

Roldolphe El-Khoury and Edward Robbins, ed., Shaping the City: Studies in History, Theory and Urban Design (Routledge). — June 1, 2013

Fresh Fields

Coupling: Pamphlet Architecure 30 Infranet Lab/Lateral Office (New York: Princeton Architectural Press) — 2011

Megabuilding

Architektura 4, 163 (Kwiecien) — 2009

In the Briar Patch

Jonathan Solomon ed., Sustain and Develop 306090 Volume 13 (New York: 306090, Inc.) — 2009

Intermediate Points of Interest

Gaby Brainard, Rustam Mehta, and Thom Moran eds., Perspecta 41 Grand Tour — 2008

Rumor

Megan Born and Lily Jencks, eds, Via: Dirt, University of Pennsylvania — 2012

The Agent: Interview with Neeraj Bhatia

The Agent No. 0 — May 1, 2014

The Knowledge

Volume 13: Ambition — 2007

Absolute Submission

Crisis, a collaboration of C-Lab and Urban China — September 15, 2008

Come to Things

Metahaven and Marina Vishmidt, eds., Uncorporate Identity (Zürich: Lars Müller) — 2010

Disposition: In_site

In_Site: A Dynamic Equilibrium, In_Site 05 (Friessen) — 2007

Foreword

Young Architects 7: Situating, catalog of Architectural League's Young Architects competition and exhibition (New York: Princeton Architectural Press) — 2006

Pandas: A Rehearsal

Cornell Journal of Architecture — 2011

Other Aggressions and Maneuvers

The Last Mile, photography catalog Satya Pemmaraju (Gallery SKE) — 2007

Subtraction

Perspecta 34: Temporary Architecture (MIT Press) — 2003

A-Ware

Journal of Architectural Education, special digital issue — January 1, 2002

Wildcards: a Game of Orgman

Metalocus 5 — 2000

Interchange and Container: The New Orgman

Perspecta 30 Settlement Patterns — 1999

A Short Contemplation on Money and Comedy

Thresholds 18 (MIT) — 1999

Distributive Protocols: Residential Formations

Beauty is Nowhere: Ethical Issues in Art and Design (Routledge) — 1998

American Town Plans excerpt

ANY — 1993

Siting Protocols

Peter Lang, ed., Suburban Discipline (Storefront Books) — 1997

Call it Home

Assemblage 24 — 1994

Perceiving Action

Offramp, SCI-ARC Journal, vol. 1, no. 5 — 1993

Switch

City Speculations (New York: Princeton Architectural Press) — 1996

Non-statecraft

Maghreb Connection: Movements of Life Across North Africa (Barcelona: ACTAR) — 2007

Graduate Sessions No. 9

Syracuse University — 2010

Not Everything

Volume 2: Not Everything — 2005

Without Claims to Purity

aX, vol. 1+2 (Winter) — 2008

Architect-at-Large

Volume 1 — 2005

The Activist Entrepreneur

John Wriedt ed., Architecture: From the Outside In (New York: Princeton Architectural Press) — 2010

With Satellites: Remote Sending in South Asia and the Middle East

Brian McGrath and Grahame Shane eds., AD, Sensing the 21st Century: Close-up and Remote Vol. 75 No. 6 — 2005

Offshore

Anselm Frank and Eyal Weizman, eds., Territories: the Frontiers of Utopia and Other Facts on the Ground (Berlin: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König) — 2004

Orgman

Stephen Graham, ed., The Cybercities Reader (London: Routledge) — 2003

Unsettling Matter Gaining Ground, Dialogue with Imani Jacqueline Brown

Carnegie Museum of Art — October 5, 2023 – January 7, 2024

The Mix

forA: Frictions — March 1, 2024