ATTTNT_Land Reparations Infrastructure

June 1, 2023 – January 1, 2024

Chicago Architecture Biennale

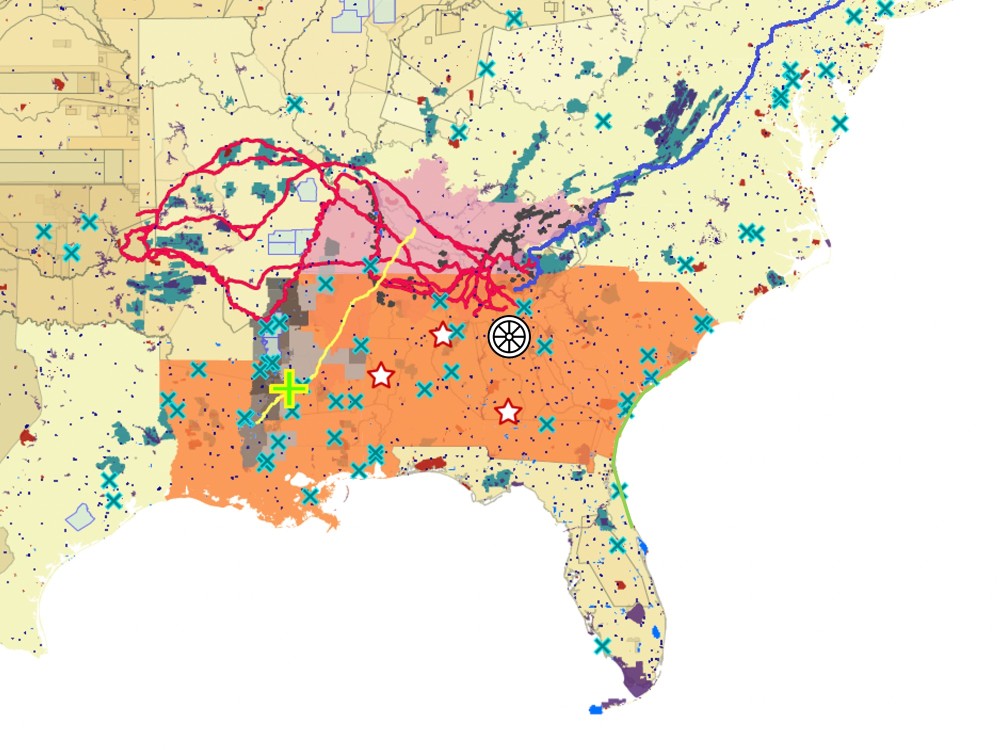

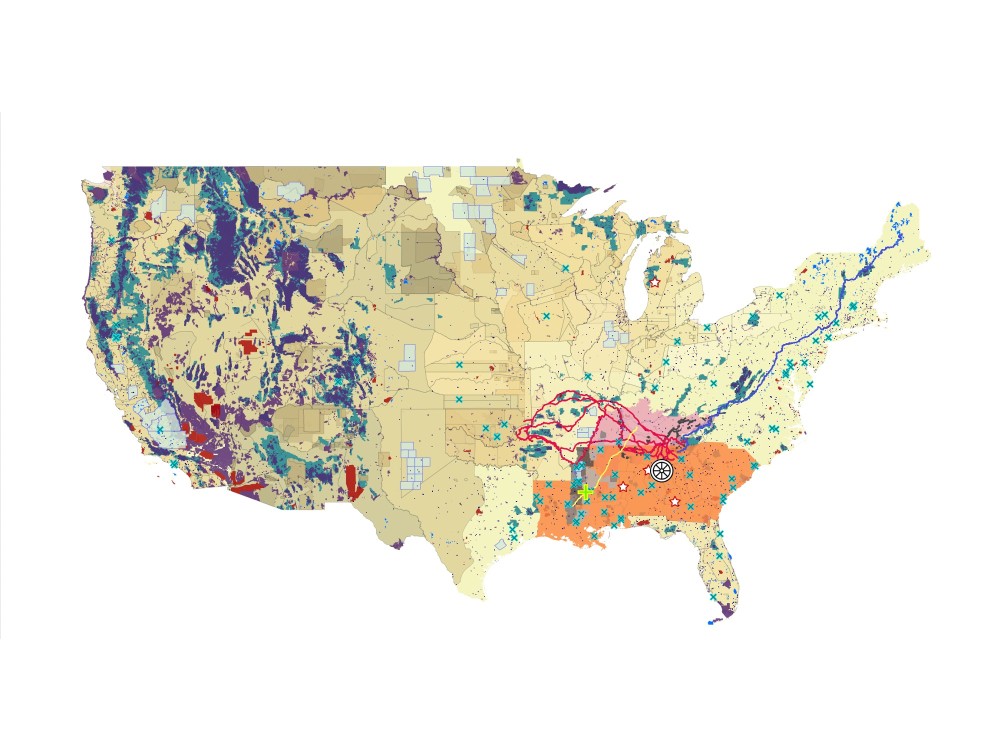

Imagine a United States organized around markings and borders different from those of state or national jurisdictions. Cobble together instead a tangled braid of lines—trails, waterways, and infrastructural corridors that deliberately revisit scars and wounds of modern programs and white supremacy.

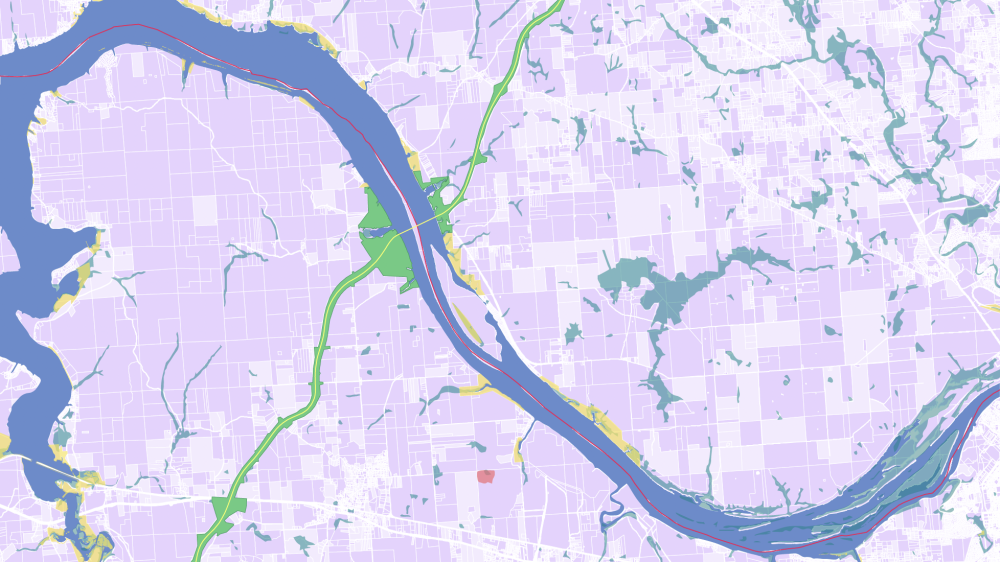

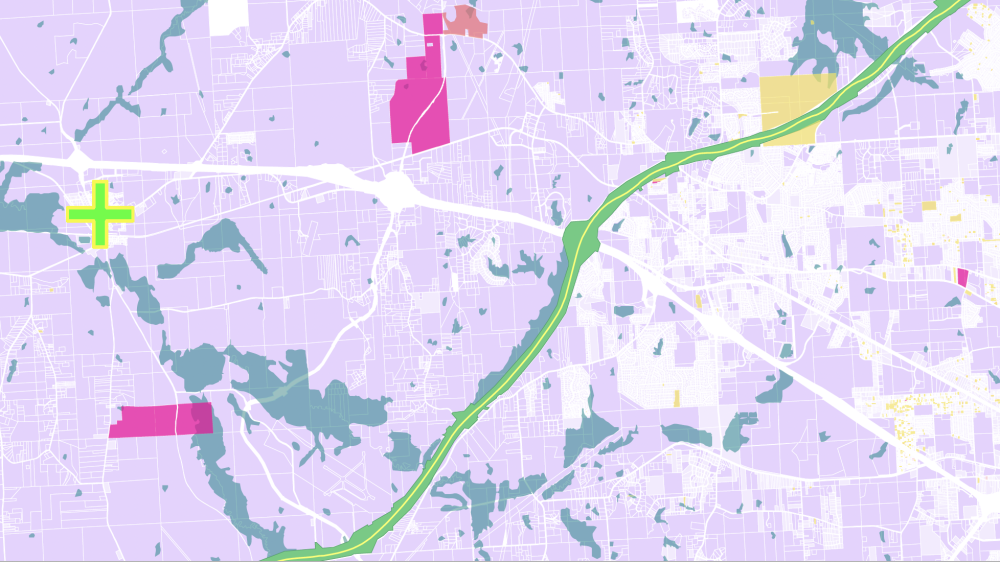

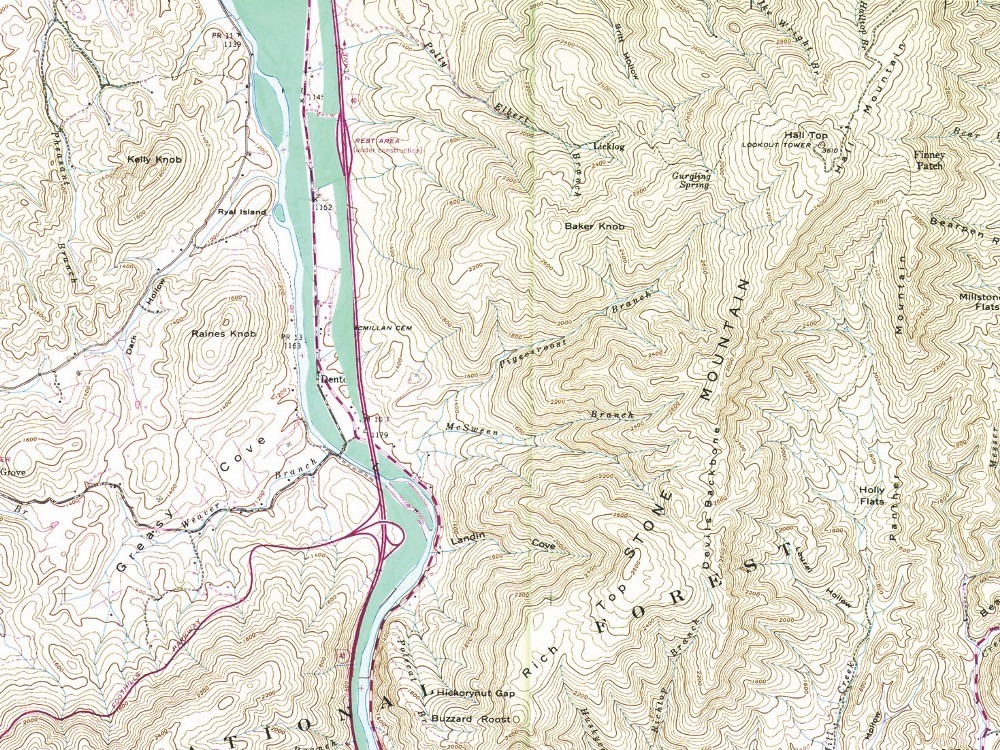

This formation might collect existing strips of public land in the US beginning with the Appalachian Trail (AT)—a 2,190-mile-long, 1,000-foot-wide, 250,000-acre corridor that stretches from Maine to northern Georgia. From the southern terminus of the AT, and using land acquired for the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), the spine of public land follows the Tennessee River, or the water route of the Trail of Tears—one strand in a network of paths used to forcibly relocate Indigenous people west after the Indian Removal Act of 1830. The line then crosses and links to a 444-mile-long, 800-foot-wide ribbon of public land along the Natchez Trace Parkway (NT)—another New Deal project marking a centuries-old footpath for Indigenous people and animals that also became a route for settlers. Continuous from Maine to the Mississippi River, this is the ATTTNT—a three thousand mile-long belt of land with six thousand miles of surface area.

While white supremacist narratives of westward expansion and modernization attended these New Deal-era projects, the ATTTNT reclaims public land to deliver another reckoning with undertold histories from the last five hundred years of Black and Indigenous resistance and survival. Since 1776, the US has stolen 1.5 billion acres from Indigenous people. And since 1910, black farmers have lost most of the fifteen million acres they owned because of white aggression and discrimination. By 1950 acreage had dropped to twelve million. By 1969, after an even more precipitous decline, it had dropped to 5.5 million. And today, the figure is less than three million acres.

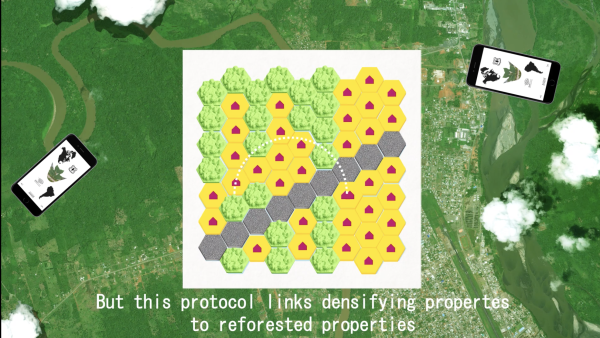

The ATTTNT does not try to smooth over its ugliness, but instead becomes more robust, lumpy and patchy as it faces this history. It only begins to take shape as reparation lands gradually thicken this infrastructure—reparations for these longstanding patterns of harm that will otherwise only continue to produce ramifying social, economic, and environmental consequences. In these last 150 years, Black and Indigenous activists have already generated a roadmap for reparations while also rehearsing the practices and institutions to manage them. This work also assembles planetary resources and solidarities that are now especially crucial in addressing root causes of climate change and inequality.

The ATTTNT also passes through parts of the South with a terrifying history of racist depravity. The project recalls crucial turning points in this history when white activists failed to go beyond their often patronizing allyship with Black leaders to establish a beachhead in their own white communities. This is work that the left has continually avoided while simultaneously asking how it can “help.” And yet the door has always been open to work on reparations. Reparations is white work. It is not the job of Black and Indigenous people to wrest the resources from a white establishment. It is the job of the white establishment to release their hold on resources that Black and Indigenous leadership have already identified to meet a long overdue and incalculable debt.

The necessarily discontinuous belts and points of land in this infrastructure might hijack the public lands of ATTTNT and claim it for a different use—as an asset to provide unorthodox access, visibility, and legibility to ongoing reparations work.

The 2023 ATTTNT mapping is a collaboration between Keller Easterling and Nicholas Arvanitis.