Envisioning Power, Corporate City, THE ZONE

May 24, 2007 – September 2, 2007

3rd International Rotterdam Biennale, Rotterdam, Holland

Zone

Some of the most radical changes to the globalizing world are written not in the language of law and diplomacy but rather in the language of architecture and urbanism.

Indeed, the notion that there is a proper forthright realm of political negotiation usually acts as the perfect camouflage for this extrastatecraft that resides in the unofficial currents of cultural and market persuasion. Capricious, hilarious and illogical, here is the rich medium of subterfuge, hoax and hyperbole that finally rules the world. From this medium emerge both epidemics of belief and prolonged stalemates. As global powers juggle national and international sovereignties or allegiances to citizens or shareholders, their behavior is, by necessity, discrepant. Theories of globalization that concoct epic binary wars between these powers (e.g. national/transnational or global/local) are nowhere near sneaky enough. It is much more likely that the multiple realms of influence are kept in play to lubricate the obfuscation so important to the maintenance of power. The nation state is not dying in the face of the increased power of transnational forces. State and non-state forces decide together how to release, shelter and launder their identity. Crucial then might be a working knowledge of the logics of duplicity rather than the practices of righteousness. While architecture and urbanism are clearly delineating some of these realms of extrastatecraft, the profession often claims to be excluded from political decision-making or claims to be “not at the table” when policy is determined. Yet the good news is that the most influential policies are controlled by discrepant characters like butlers, “go-betweens,” shills and confidence men. And architects, as the classic facilitators of power, have long been seated at that particular table.

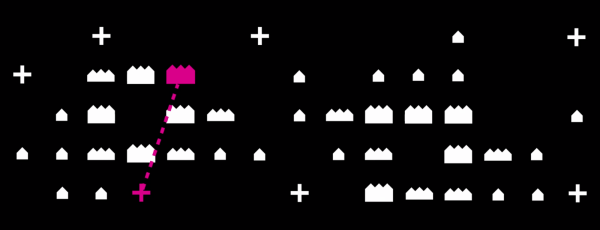

Perhaps the most vivid urban organs of architectural extrastatecraft, the technique of contemporary space-making most hidden in plain sight, is the zone.

The zone is ancient and new.

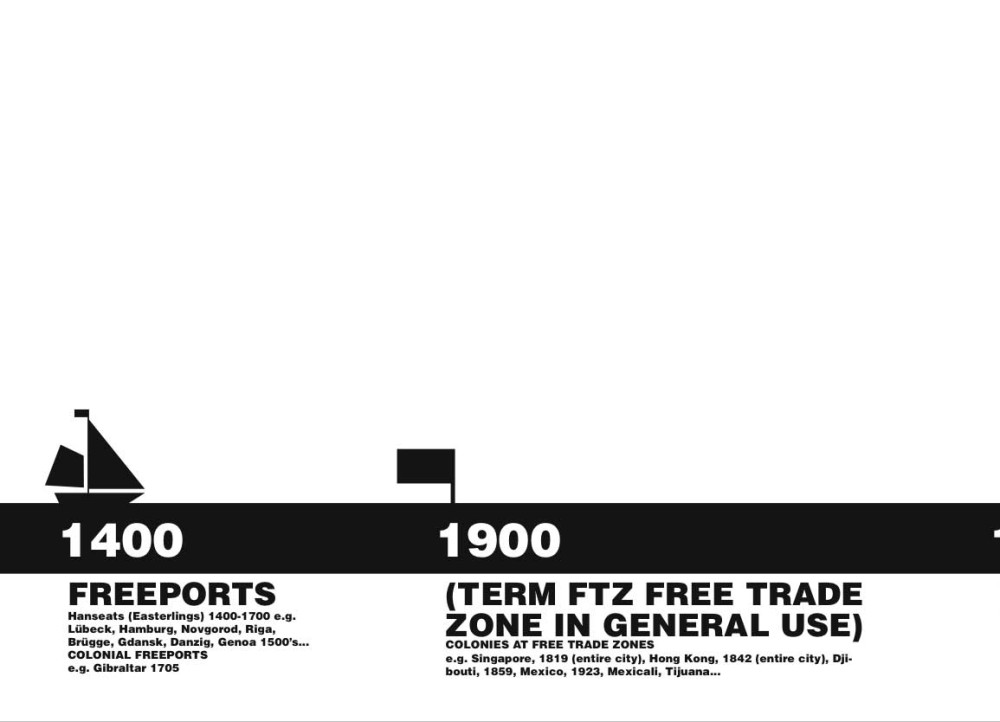

A zone may be one of any number of variants including the Foreign Trade Zone, Export Processing Zone, Special Economic Zone, Free Trade Zone or Free Economic Zone among many others. Each zone type provides its own cocktail of exemptions that might include tax exemptions, foreign ownership of property, streamlined customs and deregulation of labor or environmental regulations. Heir to ancient pirate enclaves, the freeports of the Genoa, or the ports of Hanseatic trade, the zone is the perfect legal habitat of the corporation. The earliest historical urges to incorporate express a desire for freedom and exclusivity. If it is the corporation’s legal duty to banish any obstacle to profit, and the zone is the spatial adjunct of this externalizing— a mechanism of political quarantine designed for corporate protection.

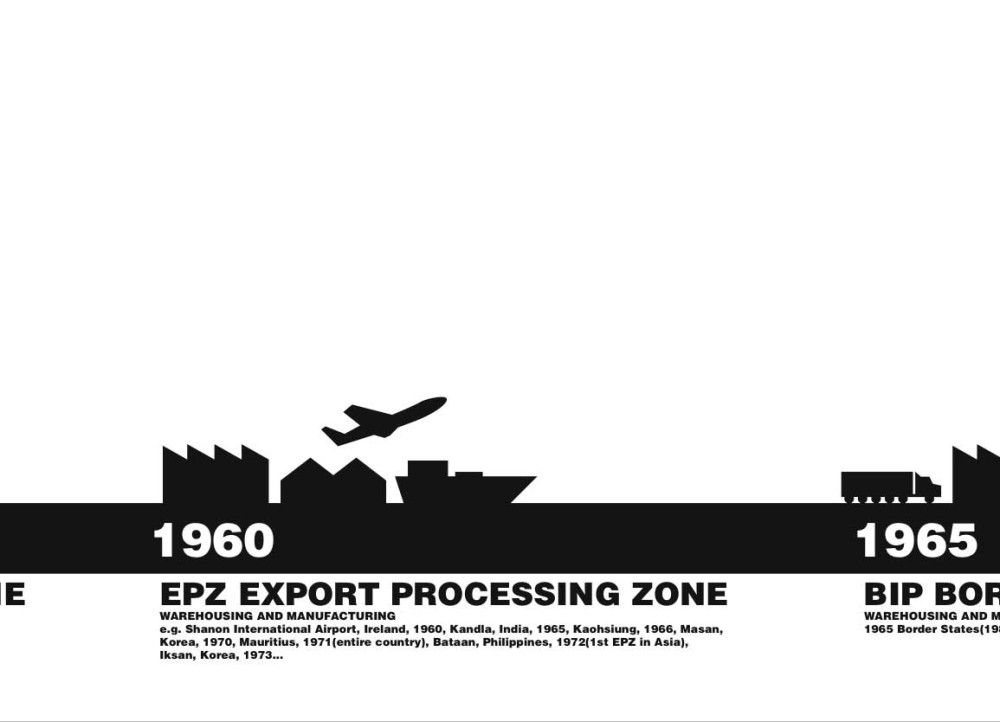

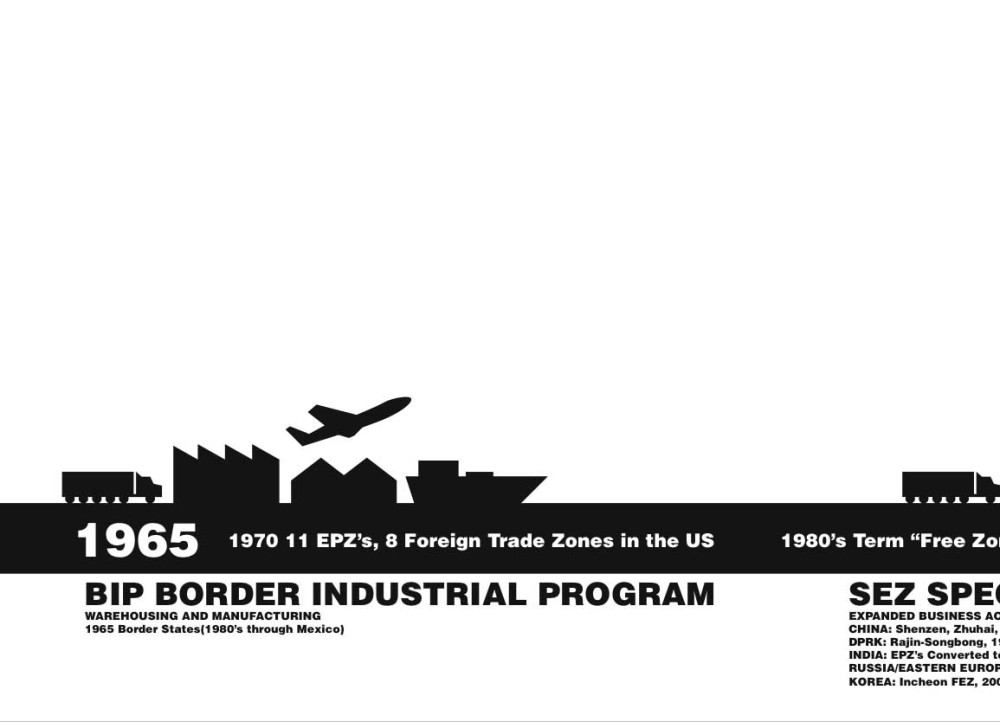

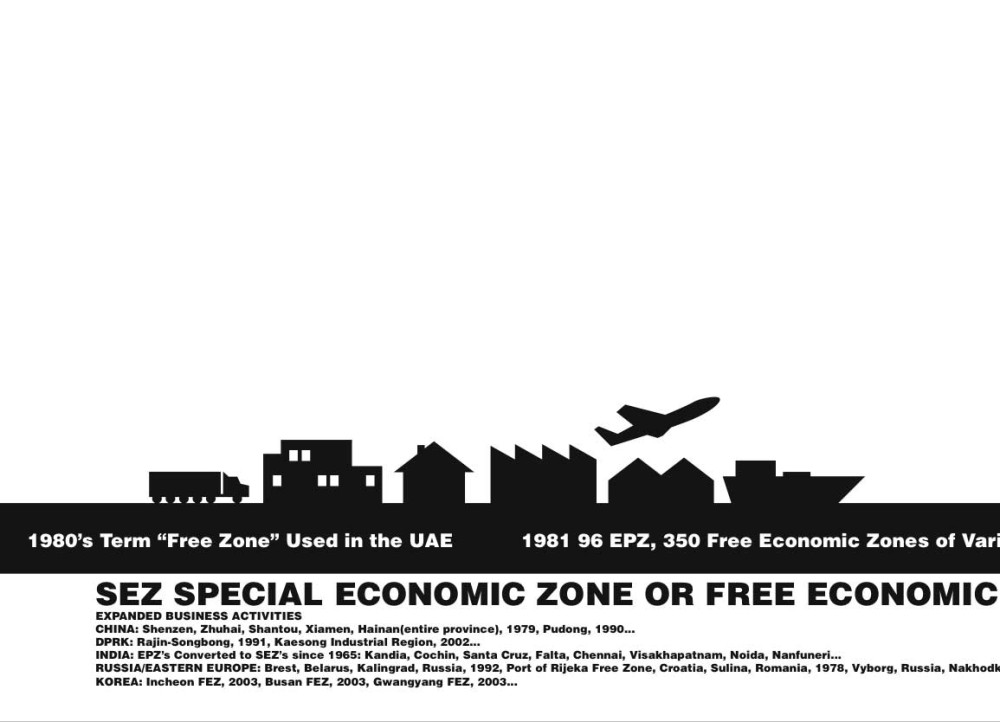

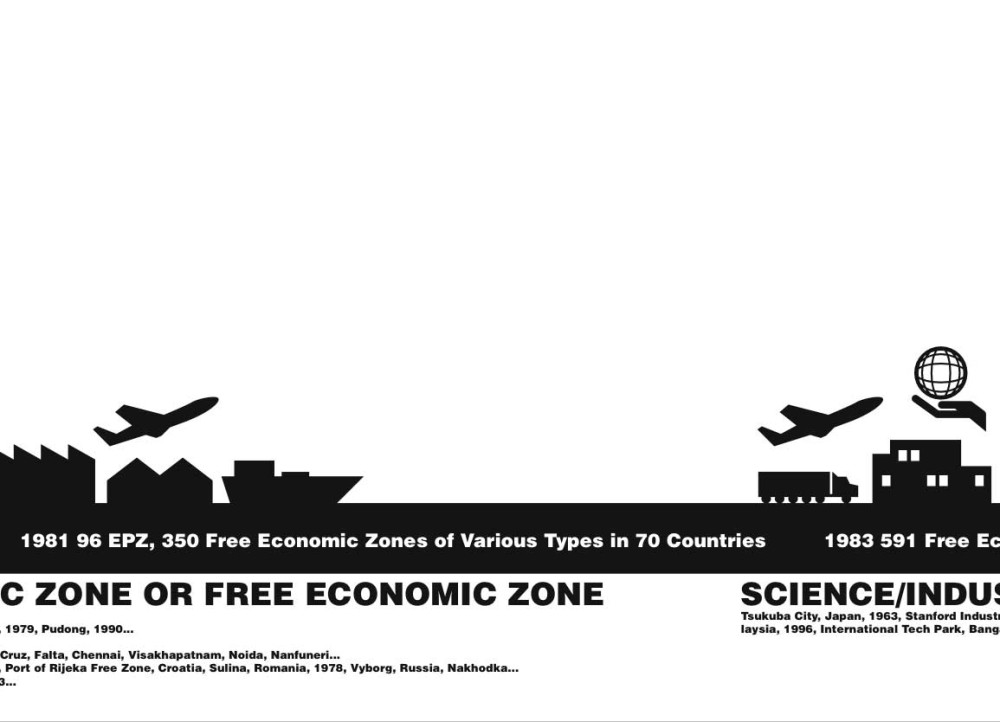

In 1934, emulating freeport laws in Hamburg and elsewhere of the late 19th century, the United States established Foreign Trade Zone status for port and warehousing areas related to trade. As the zone merged with manufacturing, Export Processing Zones appeared in the late 1950s and 60s. China’s Special Economic Zones, allowing for an even broader range of market activity, emerged in the 1970s. Since then special zones of various types have grown exponentially, from a few hundred in the 1980s to between three and four thousand operating in 130 countries in 2006. Moreover, special zones handle over a third of the world’s trade. Some zones accumulate a few hectares; some grow in conurbations that are hundreds of kilometers in size.

The zone is breeding.

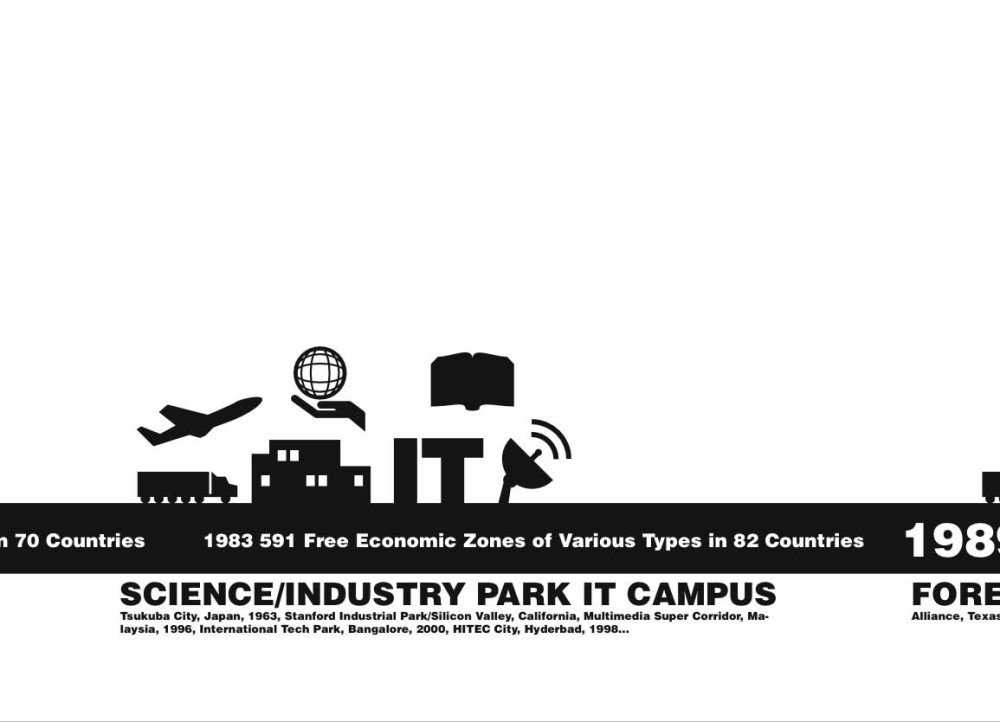

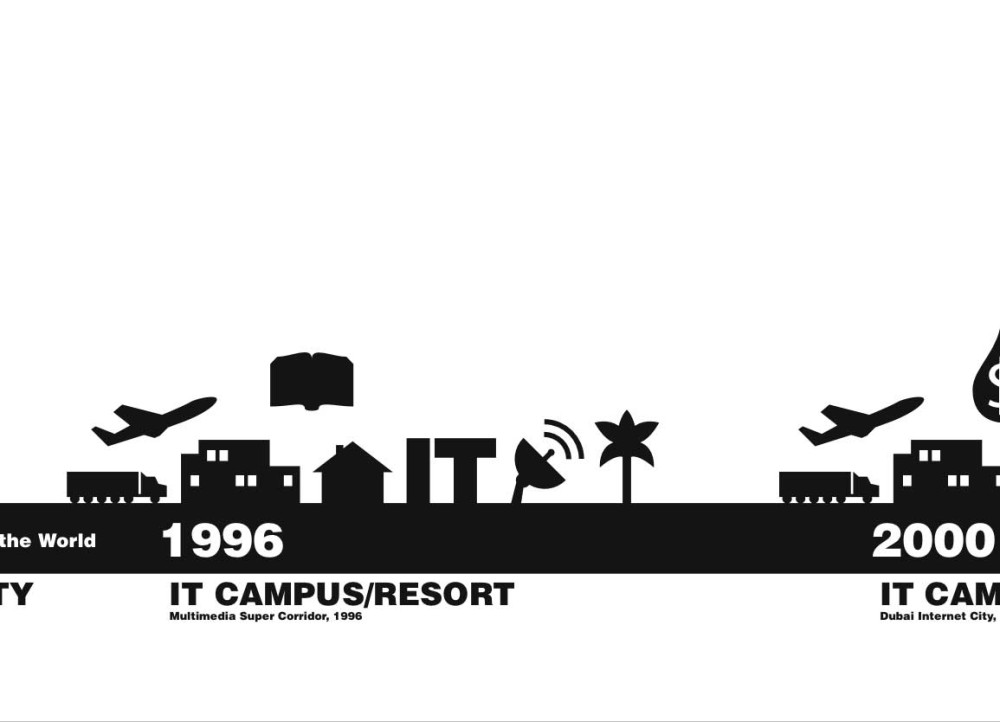

Breeding more promiscuously with other “parks” or enclave formats, the zone now merges with tourist compounds, knowledge villages, IT campuses, museums and universities that may complement the corporate headquarters or offshore facility. . The zone has become a new primordial civilization and a warm pool for the latest cocktail of spatial products (e.g. offices, factories, warehouses, calling centers software production facilities etc.) that move around the world More and more programs and spatial products thrive in legal lacunae and political quarantine, enjoying the insulation and lubrication of zone exemptions. Indeed, the zone as corporate enclave is a primary aggregate unit of many new forms of the contemporary global city, offering a “clean slate,” “one-stop” entry into the economy of a foreign country. Most banish the negotiations that are usually associated with the contingencies of urbanism—negotiations such as those concerning labor, human rights or environment—the zone is now the new urban paradigm.

Many of the new legal hybrids of zone, oscillating between visibility and invisibility, identity and anonymity, have neither been mapped nor analyzed for their disposition—their patency, exclusivity, aggression, resilience or violence.

The zone calls itself a city.

The zone often calls itself a “city,” where “city” is either a noun describing an urban area or a modifier indicating a place where something is to be found in abundance (e.g. A shopping center might be called “shopping city.”). HITEC City, Ebene Cybercity or King Abdullah Economic City, among hundreds of others, take on the title of “city” as an enthusiastic expression of the zone’s evolution beyond being merely a location for warehousing and transshipment. Many countries in South Asia, China and Africa used export processing zones as a means of announcing their entry into a global market as independent post-colonial contractors of outsourcing and off-shoring. For example, with Ebene Cybercity, Mauritius has moved beyond EPZ development to IT campus development with help from the developers of HITEC City in Hyderabad. Dubai has rehearsed the “park” or zone with almost every imaginable program beginning with Dubai Internet City in 2000, the first IT campus as free trade zone. Calling each new enclave "city," it has either planned or built Dubai Health Care City, Dubai Maritime City, Dubai Silicon Oasis, Dubai Knowledge Village, Dubai Techno Park, Dubai Media City, Dubai Outsourcing Zone, Dubai Humanitarian City, Dubai Industrial City and Dubai Textile City.

The zone is a double.

Now major cities and national capitals are engineering their own zone Doppelgangers —their own non-national territory within which to legitimize non-state transactions. World cities like Hong Kong, Singapore and Dubai, which assume the ethos of free zone for their entire territory, have become models for newly minted cities. The world capital and national capital can shadow each other, alternately exhibiting a regional cultural ethos and a global ambition. Duplicity is essential to the zone. Both state and non-state actors use the other as proxy or camouflage to create the most advantageous political or economic climate. Companies like CIDCO and SKIL can now be hired, as they were in Navi Mumbai, to deliver infrastructural, legal environments like those in Shenzhen and Pudong —city-states with not only commercial areas but a full complement of programs. New Songdo City, an expansion of the Incheon free trade territories near Seoul, is a complete international city on the Dubai or Singapore model designed by Kohn Pederson Fox. Here, aspiring to the cosmopolitan urbanity of New York, Venice and Sydney, the zone is filled with residential, cultural and educational programs in addition commercial programs. While the emotional streaming videos for the smaller “cities” of developing countries are often accompanied by tinny fanfares and low production values, the New Songdo City video messages are accompanied by new age tunes or heroic strains in the John Williams style—the spectacular theme music of the non-state capital. In Kazakhstan, in 1997, the old capital of Almaty was simply moved to the more strategic Astana, or “Astana-New City,” a core Special Economic Zone in the city featuring all the heraldic accouterment of the new capital in the form of projects designed by some of the most famous architects in the world.

The zone is beautiful, relaxed, smart and error-free; It has special stupidity.

The organizational and political constitution of the zone is often portrayed in terms of openness, relaxation and freedom The corporate city is a cleaner and smarter and more beautiful version of urbanism. Even those corporate cities that remain largely devoted to logistics, like Keppel Distripark in Singapore, win architectural awards for their beauty. Cyberport in Hong Kong, developed by Richard Li, heir to the STAR TV corporate dynasty, has developed a city so beautiful that it appears to have jumped directly from the computer screen.

The masquerade of openness effected by the lifting of any restrictive national loyalties or tariffs turns very easily to evasion, closure and enclave. Zones cheat just as most maritime city-states have cheated for centuries. Like the Mediterranean city-states of the thirteenth to the eighteenth century, with their extended networks of aggression and contraband, the port cities generate a constellation of surrounding interdependencies that may take advantage of geographic proximity but may also develop in response to distant supply chain. Whatever ancient patterns of trade and piracy reappear within the context of deregulated shipping, the maritime city is no longer a cosmopolitan marketplace but rather a society of hyper-control. It constantly oscillates between closure and reciprocity as an stretchy fortress of sorts that orchestrates controlled and advantageous cheating.

The orgmen who tend the self-referential organizations of the corporate city are proud of the fluid, robust, information-rich environments they have created. Their automated warehouses and information Landschafts slowly and obsessively sort and stack enormous amounts of information. Yet only information that is compatible to a common platform qualifies for inclusion. Indeed, an enormous intelligence is deployed to reset or eliminate any errant or extrinsic information. While remaining intact, the hermetic organization develops shrewd auxiliary tactics and strategies to fortify its stupidity and defend against contradiction. Regimes of power at once diversify their sources and contacts while consolidating and closing ranks, extending and tightening their territory. They grow while deleting information. This information paradox—wherein an enormous amount of information is required to remain information poor—might be termed special stupidity. It is a common tool of power.

The zone launders identities.

Countries just entering the marketplace may use the new zone economy, while also rejecting its incompatibility with state rhetoric or banishing it as a contradiction to the state’s purity. The DPRK introduced zones like Rajin Sonbong and Kaesong to act as cash cows for the state but also remain separate and vilified as a capitalist economy. Kim Dal Hyon (a NK economic reformer) is reported to have said, "Let’s consider the Najin-Sonbong area as a pigsty. Build a fence around it, put in karaoke, and capitalists will invest. We need only to collect earnings from the pigs." Meanwhile vast zone conurbations collect in the Tumen River Region between the DPRK and Russia. The Stalinist Dynasty of DPRK understood the way the capitalist economy works so well that they even characterized their Mount Kumgang resort near the DMZ as a “special tourist zone.” China’s SEZs are the world’s model of this phenomenon. Their early experiment with four SEZs to quarantine the capitalist market has exploded to produce scores of different zones of various types all across the country. Cross-national growth zones in the South China Sea move products between zones in different jurisdictions to take advantage of different quotas and levels of regulation. In Eastern Europe the zone allows other European corporations to take advantage of less expensive labor from entering EU countries. Similarly, AllianceTexas, north of Ft. Worth, a classic corporate city as office park and distripark, renames and redistributes many of the products produced in Mexico under NAFTA agreements so that they can be calibrated to the desired profitability in a US context.

The zone is on vacation.

The corporate city considers itself heir to the same privilege and liquidity that petrodollars enjoy. Able to materialize and dematerialize with the caprice of offshore holdings, the new corporate enclaves also need to get away and relax. Operating in a frictionless realm of exemption and merging with other urban formats, the zone also naturally merges with the resort and theme park, even assuming an ethereal aura of fantasy. Indeed if corporations are often only vessels for liberated money, they can easily be maintained outside of the work-week environment. While corporate headquarters in national capitals and financial capitals portray a glamorous business-like atmosphere, the office park in developing countries has tried to project the image of, not the hotel or club of colonial or Hilton style luxuries, but of a kingdom with unencumbered wealth. IT campuses in India and Malaysia like Multimedia Supercorridor sometimes refer to themselves as IT resorts offering lush vegetation and a mixture of small scale vernacular buildings and mirror-tiled office buildings.

Even more extreme are those corporate cities that directly merge the corporate city with the offshore island shelter. Jeju, for instance, is a quintessential island retreat that has housed, as have many islands, all of those programs or illicit activities that do not fit into the logics of the continent. Transforming itself from penal colony and strategic military position to a “free economic city.” Citing Dubai, Singapore and Hong Kong as models, the island “guarantees the maximum convenience for the free flow of people, goods and capital and for tax free business activities.” A place of ecological purity, casinos, golfer’s amnesty and mythomaniacal tradition, this corporate retreat also hosts global sporting events and diplomatic summits. On the island of Kish off the coast of Iran, Kish Free Zone similarly attracts business to the island of Kish notorious for its relaxed religious standards. Here, there is not only a loosening of headscarves and a greater opportunity for socializing between men and women, but the standard set of exemptions to which the corporation has grown accustomed. Nearby fantasy hotels like the Dariush Grand Hotel recreate the grandeur of Persian palaces with peristyle halls, gigantic cast stone sphinxes and ornate bas reliefs depicting ancient scenes. Function spatial recipes of commerce and business are not only vessels of organizational parameters, but also a medium of the many puffy fairy tales of belief that accompany power.

The zone is a parliament of extrastatecraft.

Both corporations and their infrastructures often serve paramilitary functions. Yet, it is not always nations and wars, but often massively capitalized corporate conglomerates, that create international infrastructures without any military association. Foreign direct investment is funneled not only through national treasuries but also through corporate conglomerates. From the US rail conglomerates that employed more people than the US military during the 19th century to the consortia that today operate satellite networks and submarine cable, private corporations function in an elite parastate capacity.

The zone is the parliament for the de facto global governance of this corporate headquartering. Enjoying quasi-diplomatic immunities, corporations may provide to nations the support and expertise for transportation and communication infrastructure or relationships with IMF and the World BankNetworks of construction companies and infrastructure specialists like Bouyges, Bin Laden, Mitsubishi, Kawasaki or Siemens deliver technologies for high speed rail, automated transit and skyscraper engineering. Conglomerates such as PSA, P&O, Hutchison Port Holdings or ECT, serve as modern counterparts of British or Dutch East India company franchises, delivering transshipment and warehousing technologies. Technology parks around the world grow their own satellite and cable networks with their own headquarters or embassies at the interstices of the network, whole families of corporations stick together in the same legal habitat recreated anywhere in the world and separated by a plane trip or a satellite bounce. Real estate operators like Emaar provide the spatial environments and amenities that corporate “families” recognize as a suitable location for their new corporate embassy.

The oil powers of the gulf, having re-emerged most powerfully after an historical era celebrating national sovereignty as an ultimate, more easily conflate ancient kingdoms and contemporary corporate empire with perfunctory recognition of national power. This power must be continually with media messages and architectural imagery. The largest conglomerates appear hat-in-hand in the media wanting the world to get to know them and support their work as they develop alternative energies and more resilient crops that might alleviate poverty. They ask for loyalty—a loyalty beyond brand recognition and closer to a form of patriotism for non-national sovereignty. Architects provide cosmopolitan identities, selective historical traditions, signature skyscrapersKing Abdullah Economic City, a production of the UAE’s Emaar developers on the Red Sea near Jeddah, creates yet another corporate city as world city that now offers cultural, educational, business and residential programs merged with a resort. Fly-throughs with swelling traditional music render the city as a shimmering golden man-made island filled with skyscrapers together with traditional Islamic palace buildings. The mixture of corporate and ancient imagery has, in turn, become a monument to the state and its “wise leadership.”

The zone city often uses business instruments for self-governance in lieu of the tools of a citizenry. For instance, in Dubai, a hotline is used to identify labor problems and other issues. Occasionally the new corporate city also borrows the tools of participatory democracies. Gazprom City asked the world to vote on its architectural monument from among a group of alternatives designed by famous architects.

The zone prefers non-state violence.

The prefers to benefit from an indirect association with war. Direct association is bad for business. The gulf widens between the extremes of the Dubai development model and the slums of Lagos or Kinshasa. Yet the corporate city also has a formation within which poverty can be strictly maintained without the chaos of informal economies. The offshore sweatshops in Saipan or the maquiladoras on the thickened border between the United States and Mexico organize a form of labor exploitation that is stable and within the law. The corporate city not only provides a double to the national and financial capital, it has its own double in these offshore enclaves. More discrete and less visible, these backstage formations are not given the “city” designation. They may be violent, but it is the violence of Bartelby— intractably passive and oblivious to consequences. In Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, development expertise from Abu Dhabi and Dubai is helping Alsunut Development Company Ltd. in building Almogran, which includes 1660 acres of skyscrapers and residential properties. The new corporate city only underlines the extreme discrepancies between oil wealth and the exploitation of oil resources in the mostly non-Arab southern Sudan. Indeed, the overt, even hyperbolic, expressions of oil money are among the chief tools for instigating war and violence in the south.

The zone aspires to lawlessness, but in the legal tradition of exception, it is a mongrel form that adopts looser and more cunning behaviors than those associated with an emergency of state. Commercial interests do not identify a single situation within which exception is appropriate. They move between zones concocting cocktails of legal advantage and amnesty. Just as corporate interests play a number of zone types for advantage they also operate between state and non-state jurisdictions, seeking out relaxed, extra-jurisdictional spaces (SEZs, FTZs, EPZs etc.) while also massaging legislation in the various states they occupy (NAFTA).

The zone is an intentional community.

After many cycles of zone breeding around the world, recessive or unlikely traits begin to appear. The zone as instrument of labor or environmental abuse, can, by way of its political quarantine, be filled with entirely different intentions. Dubai Humanitarian City, as an outpost of relief agencies and NGOs makes a tenant out of the chief critics of zone politics and abuses. Also, since the legal climate for each of these enclaves is designed to advantage, free speech, for instance, is permitted in Dubai Media City where the major networks are headquartered. Universities are perhaps the newest corporations to join in the zone habitat. Qatar Education City uses the campus/park/zone model to provide a headquarters for the franchise of major universities around the world. Corporate sponsorship makes of the university a kind of incubator of intelligence and manpower for the corporation as well as the region. King Abdullah Economic City will follow suit with an education sector. Saadiyat Island, a new development in Abu Dhabi will introduce not only a Guggenheim franchise and a branch of the Louvre, but an outpost of the Sorbonne.

Moreover, it is often the very attempt to maintain massive optimized realms of exemption that lands the corporate city in the cross-hairs of conflict. Shenzhen has become the unlikely cauldron of real estate survival maneuvers that borrow activist techniques associated with participatory democracy. The ports and export processing zones of the South China Sea have become the targets of international immigration and security issues that place them in the center of the political concerns they had hoped to banish.

The zone tutors impure ethical struggles.

There may be more international law to address camps like Guantanamo than there is to address most of the zone spaces in the world. The zone is an independent medium of transnational polity and multiplied sovereignty. Duplicity is the prevailing logic and organizational disposition of this space. The logics of righteousness and the insistence on orthodox political sentiment evaporate in these environments. Most urgent for architecture is not the consolidation of a singular position but rather the acquisition of an expanded, agile repertoire. While these unusual levers or toggles may not have the pedigree of political orthodoxy, they may be part of an indirect political ricochet that is instrumental in a cessation of violence, a shift in sentiment or a turn in economic fortunes.

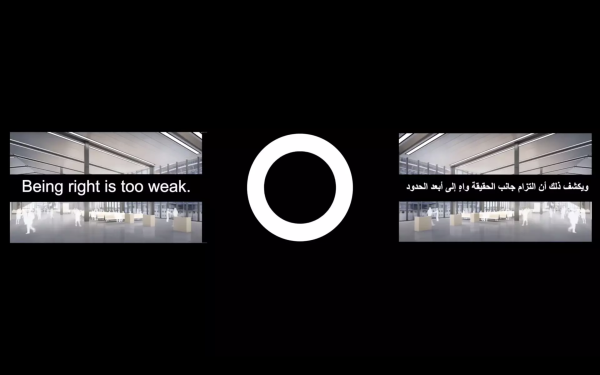

Some backstage knowledge of the bagatelle in exchange, the players in the game and the cards being dealt returns more information about the dirty tools and techniques of extrastatecraft. The zone is a discrepant territory within which to rehearse impure ethical struggles and a new species of spatio-political activism wherein curiosity and ingenuity nourish a position wherein one is too smart to be right.

Subtraction Games Lux: Projection on Beinecke Library by Lisa Albaugh and Samantha Jaff

April 10, 2015

Beinecke Library, New Haven, Connecticut